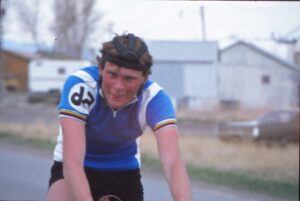

THE ENDURING LEGACY OF JON ENGEN

Jon Engen will be remembered at the 2019 Boulder Mountain Tour as the 46th annual cross country race will be held in his honor.

A three-time Olympian and avid outdoorsman, Engen died of pancreatic cancer on April 26, 2018 at the age of 61, but not before he left an indelible mark on his family, friends and the sport of cross-country skiing.

“Jon Engen was and always will be the classic stoic Norwegian skier,” said longtime friend Bob Rosso. “His love of the sport, and combined with his intensity as a highly competitive athlete always pushed many of us to go harder, ski longer, and enjoy the sport of cross-country skiing.”

With a keen intellect, competitive drive and a physical engine that was both refined and dynamic, Jon would have been right at home rubbing shoulders with the denizens of Mount Olympus.

“He was godlike,” Montana State University teammate Stuart Jennings recalled. “He just wasn’t one of the guys. He was the kind of guy if he had gone out drinking, he never had a hangover, his clothes were always just right, he never needed a haircut and I never saw a scraggle on his chin.”

Ken Robertson, another college teammate of Jon’s at MSU remarked, “Jon was a star. He was the first person I ever came across that was excellent at something. He was incredibly meticulous about everything, his gear, clothes, training, equipment, down to the tiniest detail. And he kept his eye on the ball the whole time. If someone said let’s go do something fun, Jon would evaluate it to see if it would get him down the road in some fashion. He was a whole different league.”

It is hard to say if that focus was born of nature or nurture, and perhaps it was a function of both. Born in Norway on March 9, 1957, Jon was raised an only child in Raelingen. True to the culture, Jon joined a small sports club as a four-year-old and learned how to ski and ski jump like his father, Rein. Athletic success soon followed.

“As a very young boy, Jon would win or place in long races which is kind of an anomaly in the sport. Most people don’t reach peak in endurance until they’ve been a senior for 10 years,” Jennings said.

Much like classic skis trued to the tracks, Jon’s early life followed a well-charted path: junior championships, national success, a year of mandatory military service, engineering studies at the University of Oslo, but it was during a routine visit to the dentist that Jon’s life diverged from the Norwegian norm.

“He saw photos of the Rockies in National Geographic while at the dentist and set out to get here,” wife Darlene Young said. “Applying to schools was a much different process than it is now without the internet, our schools were not full of Norwegian skiers like they are now – there was no way for him to take the SAT’s in Norway for instance. Montana State University accepted him and made him take English as a foreign language which was rather funny. Jon learned how to speak English while watching Flipper, and, then in school, he learned the Queen’s English. He spoke and wrote English better than I do.”

Joining the MSU cross country team as a 22-year-old freshman in the fall of 1979, he immediately met and became lifelong friends with Robertson and Jennings, although it was apparent to both while they have been on the same squad, Jon was no ordinary man.

“Jon had a lot of facets,” Robertson said. “He was smart, determined, and in some ways very secretive. He was a very successful racer in Norway at a young age. They had a club training program and when he came to Bozeman, he participated in team training, but most of his training was based on a secret training program that he never revealed – ever. He’d go off and do intervals and this, that, and the other, but he wasn’t going to share it. At the time it seemed reasonable enough.”

“In a race he wanted to have put in a supremely quality showing,” Jennings added. “He did not hold himself above other people, but held himself to a high standard that none of his mortal friends could match. His athletic tenacity is like nothing I have ever seen in any other athlete. His ability to dig deep and never give up was remarkable. He was that guy. He would find a way.”

As an engineer, Jon was economical with his time, thoughts and words. Stuart recalled one day after practice that Jon was unable to attend.

“Ken and I had come back to the sports area and gone to our cars to go home. I noticed Ken drove out of parking lot with maximum velocity. He had a note on the windshield of his car. It was from Jon and it said, ‘Ken, hurry home, the house is on fire. Jon.’”

The culprit was a roommate from Bergen named Knut, who had stuffed his socks between the stovepipe and the roof one too many times until his woolly insulation ignited the roof and Jon’s sense of dignity.

“Jon had a lot of national pride and felt embarrassed for his country that Knut had done this thing that didn’t reflect well on Norwegians,” Jennings said with a laugh.

That doesn’t mean Jon was without a sense of humor – although, according to some – his was so dry it could have been served with a couple of olives.

“Sometimes people didn’t realize he was joking with them but I thought his sense of humor was hysterical. He had a unique insight into and understanding of human nature,” Darlene observed.

Graduating in 1983 with a degree in Civil Engineering, Jon continued training as a biathlete and cross country skier,

Mike Wolter, a longtime Ketchum resident, who also attended and raced for Montana State University, remarked, “I met Jon right after I got there in 1983. We spent a lot of time skiing, training, exploring Montana and participating in obscure running races. There was a race we did on Beartooth Pass and we brought our skis and went skiing after the race. He was an animal then and an animal his whole life.”

“It’s the Bridger Ridge Run,” Jennings said. “It’s a 20-mile mountain run (billed as a race “only for the truly physically fit”) on a poorly developed trail. He won that race more times than anyone and it was something he did as training.”

Jon continued to wedge his training in when he could – despite a full-time job as an engineer – and as a newly-minted American kept his eyes on his goal to represent his adopted country at the Olympics. According to Robertson, Jon shoehorned training in on nights and weekends – often roller skiing in the dark – while working 40 hours a week in Billings. His initial goal was to make the Olympic Biathlon Team, but when things didn’t pan out at the windy trials, Jon set his sights on a new goal, the Olympic Cross Country Team.

Jennings fleshed out their Olympic odyssey.

“We both trained for the ‘88 games as biathletes. We didn’t make it. The cross-country tryouts came later in January and I said to him, “You know I am spent. I will go and be your coach.” I went with Jon to tryouts in cross country as a coach. As an outsider, he had no splits or wax support from national team coaches. He had no funding and was working a career-type job.”

Bill Spencer was also on the bubble in Biwabik, Minnesota, and credits Jon with getting him over the top and on the Olympic team.

“It came down to a 50k skate race for a few of us. I had a couple classic races where I didn’t do well. I had seriously overtrained and knew that my only chance to make the team was to do well in this one race. Right out of the gate, I just wasn’t feeling good and my splits were not that great. Jon had started three minutes behind me on a pretty hilly course. About 5k in he comes chugging up the course and caught me. I hooked in behind him and he towed me for the next 45k. I went from 15th to third and Jon won quite handily,” Spencer said.

“He was very proud to make the team,” Jennings remarked.

And to represent his new country, according to Wolter, “He was proud to be an American and proud of being from Norway. He waved both flags.”

A few years ago, Jon told Eye on Sun Valley online news, ‘There is no other challenge like the Olympics if you want to be with people who are successful. One thing about the Olympics is everybody there has a story. It’s not about run-of-the-mill people. Most athletes are creative scrappers.’

“I think the number of people working 40 hours a week who make the Olympics is next to zero,” Robertson stated.

Jon’s best finish at the 1988 Winter Games in Calgary was 51st in a 30k mass start. He redirected his training to biathlon, noting, ‘I’m a better shooter than cross country skier’ and competed in the 1992 Olympics in Albertville, France, and the 1994 Olympics in his native Norway at Lillehammer. His best individual finish was a 64th in a 20k in his native country, despite being one of the oldest competitors on the team at 37.

“Skiing was in his blood. It is what he knew,” Darlene said.

With every quality it took to be a world-class athlete, and several top-20 finishes in World Cup races in both sports, Jennings believes the one thing that prevented Jon from being the best in the world came from a lack of financial support given to nordic and biathlon athletes.

“Had there been support for him to train full time, he would have had that extra percent. Lowell Bailey (the first American to win a biathlon world championship) reminds be a lot of Jon. It comes down to the level of support we have for nordic and biathlon.”

Despite the inherent challenges, Jon’s love of sport never waned and he went on to race on the international and national master’s level capturing more than 20 World Cup Master’s medals with 12 gold, including two golds in the 24th Masters World Cup Nordic Championships in 2004 at Lillehammer.

A lifelong Rossignol team member, Jon’s athletic prowess was remembered by former Rossignol USA Nordic race director Jim Fredericks in remarks to the Idaho Mountain Express newspaper.

“Jon was a fierce competitor and well known on the ski circuit, whether it was biathlon, marathon skiing or the U.S. cross-country national circuit. As a competitor, Jon was well liked but also feared by his competitors. Many elite and younger racers were often schooled by Jon as he passed them in races. However, his humble demeanor outside of competition contributed to his popularity off the ski course.”

“I still remember the one race where I nipped him at the finish, it was a 25k at the West Yellowstone Rendezvous,” Wolter said. “We went back and forth the whole race and I got him by a ski tip at the end. I’m not sure he believed it, but he was always respectful and always the first one to compliment someone.”

The ability to extend admiration in the form of a compliment served Jon well when crossed paths and fate with Darlene Young at the Boulder Mountain Tour.

“We met in 2000 at the Boulder Mountain Tour banquet. Well, we actually didn’t meet, he saw me there. He wrote me an email a few weeks later saying that, ‘while at the Boulder Mountain Tour I noticed that you have a fantastic smile.’ What girl couldn’t fall for that?”

Robertson recalled that Jon also shared his feelings about Darlene with him, displaying his understated humor that belied a deeper seriousness.

“Shortly before he moved to Sun Valley, he had been to some ski race and met Darlene. Jon was not one to ever talk about women, he was really private, and super circumspect. He said to me, ‘Yeah, I met this woman Darlene and an independent panel of experts voted her as having the best legs of anyone at the race.’ I knew he was head over heels for her after that.”

Jon moved to Sun Valley in 2002, and the pair married in 2006.

“Darlene was the love of his life,” Jennings said.

Jon was a fixture in the Boulder Mountain Tour, and perennially challenged the elite field despite giving up a decade or two to the younger men. The Idaho Mountain Express reported that, “In one unforgettable and lightening-fast BMT on the 32-kilometer course in 2003, Men’s 45-49 class winner Engen finished sixth, just two seconds off the top time – in a pack of racers who were 15 to 20 years younger than he was.”

“(He was) Superman in mind and body,” Darlene said.

In addition to his love of snowsports, Jon was equally acclimated to the other seasons and a devotee of cycling, trail running, hiking, and hunting with his dog, Bamse.

“Jon bonded very well with the western lifestyle. He liked being out in the woods. We spent many days of hunting,” Jennings recalled. “One time we had gone to this place with good elk hunting. We were sitting in meadow at dusk, but in different parts of the field. A herd of elk came running in with a 6-point bull elk at back. I flipped off the shot. Jon was incredulous, ‘Why didn’t you shoot the cow elk?’ I said why should I, I shot the bull. And he said, ‘no, I shot the bull.’ We found both bullets. We shot him at the same time. So we split him.”

Dedicated to giving back to a sport that had given so much to him, Jon founded the Sun Valley Masters Nordic Ski program, was a valued instructor for Sun Valley Company for 15 years, a coach for Team Rossignol and led trips to the World Masters Championships among a myriad of other endeavors, and was inducted into the Sun Valley Ski Hall of Fame in 2014.

“While he still competed as an adult he really felt he was done with that aspect of his athletic career and wanted to do things he had never done. He just really enjoyed being able to get out and be active,” Darlene said. “He was generous with his time and had a positive impact on many. He was there to help whenever anyone asked.”

Fredericks added, “While skiing for Team Rossignol, his teammates often looked up to Jon for his expertise in training and technique. Many of those racers still credit Jon’s coaching as a contributing factor in their success.”

Wolter concurred, “He had such incredible knowledge of the sport and athletics in general and was always digging and looking for things. He was passionate and gave good advice,”

Jon also served as a board member for the U.S. Ski and Snowboard Association, and chaired USSA’s Cross-Country Sport Committee from 2006-2014. In both roles, Jon brought his expertise as an athlete, coach and industry representative to spur the growth of U.S. skiing and is regarded as one of the committee’s most impactful leaders. He received a Special Recognition Award from USSA at the end of his term.

“Much of the success we are enjoying now in cross-country skiing stems from the period when Jon’s committee and community leadership played a major role in the growth of the sport in America,” USSA Chief of Sport Luke Bodensteiner stated. “Most of all, he was just an amazing, kind individual who just wanted to help the sport find success in America.”

In August of 2017, cancer knocked on Jon’s door. Jon, Darlene, family and friends were stunned.

“He was surprised when he got cancer. He had no risk factors,” Jennings said. “But it was just one of the challenges in his life that he was going to overcome. He never came across anything in his life where he couldn’t excel. He was going to win.”

Jennings added that Jon developed a regimen, similar to his secret training program in college, that be believed would help him beat cancer, “I need to focus on the program,” Jon would say, while sending visitors out of his hospital room.

That belief in self. The unyielding will remained with Jon until it was clear cancer was a foe that would not be vanquished. What remained untouched was his heart, mind and spirit, everything that was inherent and instructive to who he was and what he did.

“His mind never left. He had an incredible memory and even when he was weak and it was hard to talk he was sharp,” Wolter recalled. “The last time I said farewell to him he said, ‘Can you believe you are looking at the same person?’ I could not. But he still cracked a smile and had a gleam at the end.”

“He said that life was too precious to give up and never gave up hope that he could beat it. I think everyone thought if anyone could do it, he could. His passing stunned many as we all believed with him,” Darlene said, adding, “Jon believed in me better than I believed in myself. I think he had that effect on many. He was a coach, mentor and supporter of so many.

“And if he could see the love that came in from all around the world after he passed away, I know that would have made him truly happy.”

Earlier this summer, Darlene accepted the prestigious Al Merrill Nordic Award on Jon’s behalf. The honor is given to the individual (or group) involved with any aspect of Nordic skiing who demonstrates an exceptional level of commitment, leadership and devotion to excellence.

An unparalleled ambassador of the sport, Engen’s love of cross country skiing was only exceeded by his regard for his fellow man. Fiercely intelligent, dedicated, and determined were characteristics equaled by a relentless passion for life, the outdoors and athletic pursuits. It is in his honor and these traits he shared so generously with others, the Boulder Mountain Tour is proud to host the 2019 race in Jon’s indelible memory.

– Jody Zarkos